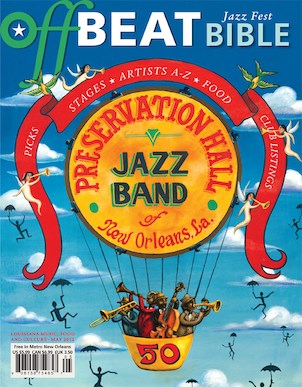

Preservation Hall 2.0

Within the span of two days, music fans attending this year’s Jazz Fest will have the extremely rare opportunity to time-travel more than a half a century, in some cases close to a whole century. It’s easy. Hear the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in the festival’s traditional jazz venue, Economy Hall, on Saturday, May 5, and then go hear them on Sunday, May 6, when they will take to the Gentilly Stage as the Preservation Hall Jazz Band and Friends. That show is essentially a continuation of their 50th anniversary concert at Carnegie Hall on December 7, 2011, which itself was essentially a continuation of their 2010 release, Preservation, on which old-timers including Merle Haggard and Tom Waits trade guest appearances with rockers such as Jim James and Jason Isbell, folkies Pete Seeger and Ani DiFranco, Paolo Nutini from Scotland, the Blind Boys of Alabama, the Del McCoury Band, Dr. John, Angelique Kidjo and so on.

Who might appear on stage Sunday? Several artists have been announced: Allen Toussaint, Trombone Shorty, the Rebirth Brass Band, Bonnie Raitt, Jim James, Steve Earle, Ani DiFranco, Wendell Eugene, Lionel Ferbos, and Jazz Fest founding producer George Wein, but there may be more. Guessing possible “surprise” guest artists is a favorite Jazz Fest pursuit, but think who you’re guessing about. The Preservation Hall Jazz Band. When’s the last time you dialed them up on your iPod? How’d the Preservation Hall Jazz Band suddenly get hip?

L-R: Clint Maedgen, Rickie Monie, Charlie Gabriel, Ben Jaffe. Photo by Golden Richard III.

It didn’t. Suddenly, that is. It’s taken almost 20 years to turn what had been a smooth-sailing, well-oiled machine from its cruise across the seas of nostalgia toward what would most certainly have been the junkyard where old cultural movements go to die, and point it toward a new future with a larger mission. Credit for that achievement goes to Ben Jaffe, who didn’t exactly inherit the family business, but he ended up running it anyway. Ben’s father, Allan, formally accepted responsibility for running the Hall (eventually purchasing it) with his bride, Sandra, in June 1961. The couple spent the next 30 or so years creating and maintaining what soon became a central and colorful American institution—an old, dusty building in the French Quarter where old, black men who still remembered the early years of jazz came to play every night, while another band, similarly composed, toured the world, becoming regulars at summer music series and festivals.

All was running smoothly until the unforeseen occurred: Allan Jaffe died of a heart attack in 1987 at the unfortunately young age of 53. Ben was just a junior in high school, and his mother shipped him off to college to have a life of his own while she and her sister and some of their friends ran the Hall. Ben gravitated toward music, playing his father’s instrument, the bass, but majoring in modern jazz at Oberlin Conservatory and booking his own “neoclassical” modern combo in local cities on weekends. The summer he graduated, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band’s bassist became too ill to travel, and Ben joined the band to play tuba and bass, beginning with a six-week residency in Paris. When he returned, he knew instinctively that running the Hall would be his life’s work. No words were ever spoken, no contracts signed. It’s a family business, so Ben still needs family approval. But that’s never been much of a problem since most of what he’s done has happened organically, one change at a time. Slowly and methodically, he changed the make-up of the band and eventually the very definition of the Hall, moving it from within the narrow confines of jazz history into the wide, open world of American roots music.

“When I took over responsibility for managing Preservation Hall, I was only 22,” Ben told writer Alison Fensterstock recently. “I was petrified that we’d cease to exist when the original band passed away.” In his first two years at the helm, that’s exactly what happened. Willie Humphrey, the 93-year-old lyrical clarinetist who’d been associated with the Hall since its founding in 1961 passed away in the summer of 1994. His younger brother, Percy, the trumpeter who’d been a solid and reliable bandleader since the Hall’s founding, passed away the following summer at the age of 90. “For the first six or eight years,” Jaffe recalls, “I’d have to spend half an hour after every show talking to fans about the band and what was going to happen now that Percy and Willie were gone. Some of these folks had been following the band for 20 or 30 years.

“Somewhere in the late 1990s, I realized what they really wanted was to experience New Orleans’ unique musical traditions. Over the years, Preservation Hall had come to represent those traditions in a very specific way. When I was growing up, I experienced New Orleans music as a living, breathing organism. The more I recognized Preservation Hall’s role in keeping New Orleans’ music traditions alive, the more I realized the way those traditions were being represented would have to change. And the audience would have to change. When I joined the Preservation Hall band, it was rare that you’d find anyone in our audience under 60 years old. It was a very mature audience.”

The changes began as Jaffe resurrected the Hall’s recording label. He began importing new music and new musicians into the band, recruiting most notably Clint Maedgen from the New Orleans Bingo! Show on vocals and saxophone. Around the same time, the two collaborated on a version of the Kinks’ “Complicated Life.” Long-time fans found such decisions heretical.

“I knew this wouldn’t be easy,” Jaffe says. “I knew that to find new audiences, people weren’t going to come to me, I would have to go to them. And I knew that change on this level might upset and confuse a lot of people, but I decided if I was going to fail at this, at least I would fail doing what I knew in my heart was right.”

Then came Hurricane Katrina, and Jaffe spent the next couple of years deeply immersed in relief efforts, raising more than $3 million and helping start a non-profit social service agency, Sweet Home New Orleans, that continues to provide service to local musicians in need.

Just as relief efforts were dying down and recovery efforts beginning to ramp up, a friend of Jaffe’s approached him with the idea of doing a high-profile benefit album featuring the Preservation Hall Jazz Band and a roster of guest artists. Jaffe took his friend up on her offer but directed proceeds to The Preservation Hall Outreach Program—an effort to introduce young people to the music and encourage their efforts in perpetuating it. Preservation (its unwieldy full title: Preservation: An Album Benefiting Preservation Hall and Its Music Outreach Program) received quite a bit of attention and led the way to a 50th-anniversary celebration in 2011 that played out the full range of potential cultural celebration inherent in an institution like Preservation Hall: art and history exhibitions; dance and theater collaborations; music mash-ups and joint tours.

After recording nearly all the Preservation tracks in the Hall’s front performance room, the space itself seems to have come alive. After the BP oil spill, Jaffe, the band, Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def), Trombone Shorty, Lenny Kravitz and the actor Tim Robbins gathered there to record a rap/trad jazz protest song based on the Wardell Quezergue and Smokey Johnson classic, “It Ain’t My Fault.” When Amy Winehouse music producer Mark Ronson set out to lay down his track for the recent Grammy-sponsored documentary Re:Generation, he, along with Bey, Erykah Badu, the Dap-Kings, Trombone Shorty, and Zigaboo Modeliste ended up playing a party at the Hall. During the past two Jazz Fests, the hottest tickets outside the Fair Grounds were for shows at the Hall. Two years ago, Jim James and My Morning Jacket brought the rock world’s attention to the Hall with what was, by all accounts a mesmerizing show followed by a 3 a.m. parade around the empty streets of the French Quarter, and last year Robert Plant made an unscheduled appearance at the Saturday Night show headlined by guitarist Buddy Miller, his music director.

As if to confirm its status as an essential American roots band, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band was featured this past October on Austin City Limits with guests Jim James and the Del McCoury Band.

Jaffe insists that music fans who check out the Economy Hall set the day before won’t hear much difference in the music being played. The real difference, he says, will be in the make-up of the two audiences. And in that, he’s mostly right. The Preservation Hall Jazz Band continues to play in the same tradition that prevailed in the years when it was founded. For some people, that’s a tradition set in stone, never to be varied, but traditions have to breathe to live, and all Jaffe has done is set Preservation Hall free from a set of responses that are no longer as effective as they once were. Repositioned as an American roots institution still very much alive and well, New Orleans Preservation Hall and its world-traveling jazz band—even at the ripe old age of 50—are back on the American music radar in a major way.

Preservation Hall Jazz Band plays Jazz Fest on Saturday, May 5 at 4:25 p.m. on the People’s Health Economy Hall Stage and on Sunday, May 6 at 5:35 p.m. on the Gentilly Stage.

No comments:

Post a Comment